Conway's Game of Life

Yesterday I was talking with my wife about the chaos in life. How complex are the systems? How insane is thinking that we are, for instance, only one event from our life goal? Or, in her case, how could only one post be a life-changing moment? Thinking about that, I remember Conway’s game. She holds a degree in biological science. So, the conversation about life complexity was inevitable.

After that, I realized that I had never coded Conway’s Game of Life. So, today I will do it. It will not be the best implementation or the most effective version. It is just an exercise. Furthermore, in the future, I will spend time coding a continuous implementation of Conway’s game.

An overview

The Game of Life is a simple grid-based game that reflects deep philosophical concepts. It shows how complex patterns can emerge from basic rules, mirroring the order and chaos in life.

It also reminds us of the transient nature of existence, as cells can die or be born based on their surroundings.

The game raises questions about determinism and free will, as emergent patterns have an unpredictable element. Overall, it invites us to ponder the mysteries of life and appreciate the beauty that arises from simple interactions.

In the Game of Life, the grid consists of an infinite two-dimensional array of square cells. Each cell can be either “alive” or “dead.” The game evolves in discrete time steps, where a set of rules determines the state of each cell in the grid.

The rules of the Game of Life are as follows:

- Birth: A dead cell with exactly three neighboring live cells becomes alive in the next generation.

- Death by isolation: An alive cell with fewer than two live neighbors dies due to underpopulation in the next generation.

- Death by overcrowding: An alive cell with more than three live neighbors dies due to overcrowding in the next generation.

- Survival: An alive cell with two or three live neighbors survives to the next generation.

The game starts with an initial configuration of live and dead cells on the grid. After the initial setup, the game progresses iteratively, with each generation being determined by applying the rules to the previous generation.

The interesting aspect of the Game of Life is those simple initial configurations can lead to complex and unpredictable patterns. Some patterns may stabilize into static structures, while others may oscillate or move across the grid (a.k.a gliders).

The code

The approach is very simple. Create a randomly (0 and 1) initialized grid, then iterate through generations computing the deaths and births.

To create the grid, I defined the World struct as follows:

enum class CellState { DEAD, ALIVE };

struct World {

public:

World() {}

void update() {

updateWorld();

drawWorld();

}

private:

std::array<std::array<CellState, SIZE>, SIZE> _cells;

unsigned int countNeighbours(const unsigned int x, const unsigned int y) {}

void updateWorld() {}

void drawWorld() {}

};

The grid (_cells) has a squared size of SIZE and was built with a two-dimensional array. Each cell holds the value of its state as CellState::DEAD or CellState::ALIVE.

The constructor populates the World through the GOD seeds.

unsigned GOD = std::chrono::system_clock::now().time_since_epoch().count();

std::default_random_engine generator(GOD);

std::mt19937 mt(GOD);

std::uniform_int_distribution<int> distribution(0, 1);

CellState randomState() { return static_cast<CellState>(distribution(mt)); }

World::World() {

for (auto &row : _cells) {

for (auto &cell : row) {

cell = randomState();

}

}

}

Then, will draw the grid on the screen.

const std::string SYMBOLS{" *"};

void World::drawWorld() {

std::ostringstream oss;

for (auto row : _cells) {

for (auto cell : row) {

oss << SYMBOLS[static_cast<unsigned int>(cell)] << " ";

}

oss << "\n";

}

system("clear");

std::cout << oss.str();

}

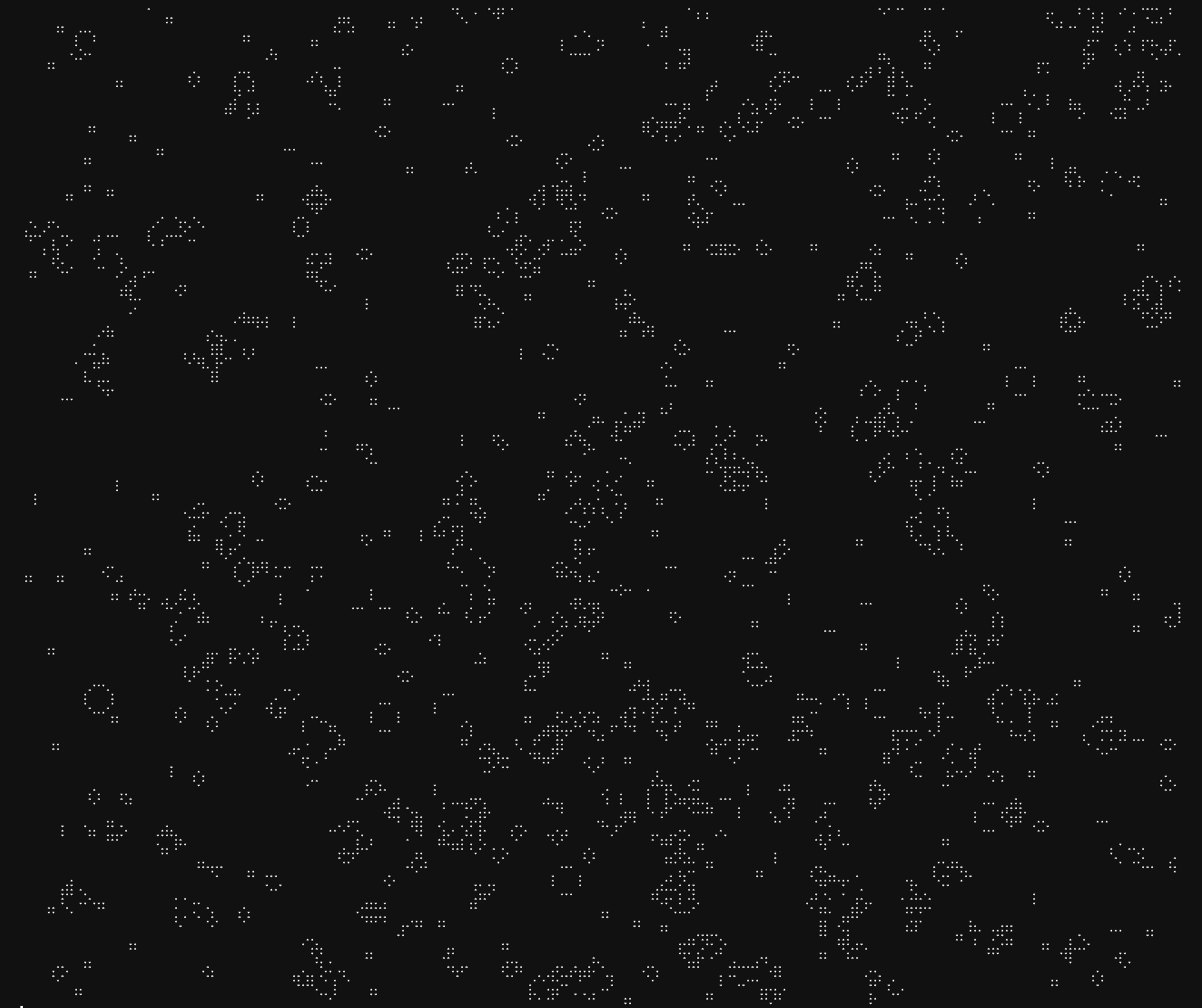

Yeah, here we could see things starting to happen.

* * *

* *

* * * *

* * * * * * *

*

* * * * * *

* *

* * * * * *

* *

* * * *

* * * * * * * * * *

* * * *

* * * *

* * * * * *

* * * * * *

gbs@gojira:~/fun/blog/cpp/game-of-life $

Now, we need to create the generations and the survival rules. As described above, the rules are pretty simple. They are based on how many neighbors each cell has. Each cell is surrounded by eight other cells (except the borders).

unsigned int World::countNeighbours(const unsigned int x, const unsigned int y) {

auto neighbours = 0u;

for (auto i = x - 1; i <= x + 1; i++) {

for (auto j = y - 1; j <= y + 1; j++) {

if ((i == x && j == y) || (i < 0 || j < 0) ||

(i >= SIZE || j >= SIZE)) {

continue;

}

if (_cells[i][j] == CellState::ALIVE) {

neighbours++;

}

}

}

return neighbours;

}

One tricky part here is that the entire grid is calculated in one single step. So, we may not alter the grid while still computing the survival rule. The obvious alternative is to spend more memory creating another grid to hold the new generation.

void World::updateWorld() {

for (auto x = 0; x < SIZE; x++) {

for (auto y = 0; y < SIZE; y++) {

auto neighbours = countNeighbours(x, y);

if (_cells[x][y] == CellState::ALIVE) {

if (neighbours == 2 || neighbours == 3) {

_newCells[x][y] = CellState::ALIVE;

} else if (neighbours > 3 || neighbours < 2) {

_newCells[x][y] = CellState::DEAD;

}

} else {

if (neighbours == 3) {

_newCells[x][y] = CellState::ALIVE;

}

}

}

}

_cells = _newCells;

}